In “Raw Material,” for instance, a pair of exquisite descriptions of Victorian housework-“How We Used To Black-Lead Stoves” and “Wash Day”-are enclosed in a semisatirical melodrama about a creative writing teacher and his students. Disdaining the austerity of modernism, Byatt leaps forward to postmodernism, with its framing devices and art about art. As readers of Possession and Angels and Insects (1993) know, she has an affinity for the Victorian era in “Precipice-Encurled,” an ambitious young painter falls in love with the young lady he’s sketching before losing more than just his heart as he pursues a visual idea inspired by one of Monsieur Monet’s new paintings. These stories, selected from periodicals and previous collections, present compact versions of her favored themes, preoccupations, strengths, and occasionally weaknesses, and they’re short enough that her densely decorative prose rarely grows wearisome. A little of this can go a long way (though, as the novels demonstrate, sometimes a lot can go even further).

She favors adjective-spangled cascades of images, excavates the dictionary for rare specimens, and sends iambs and anapests cavorting across the paragraphs.

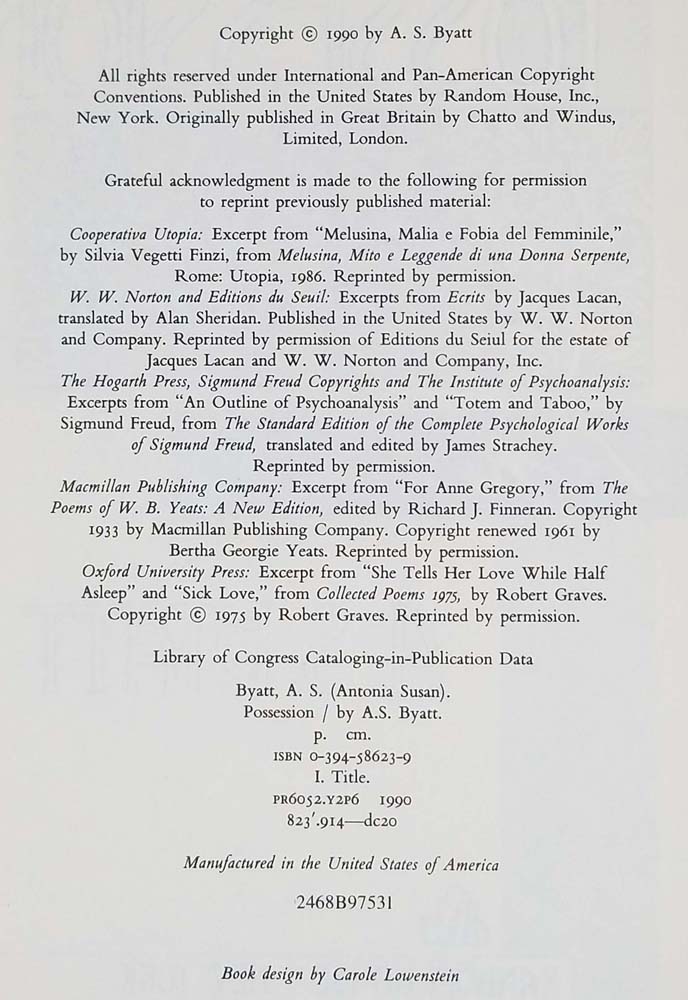

A career-spanning selection of short stories from one of England’s distinctive voices.īyatt is known for her novels-especially the Booker Prize–winning Possession (1990)-but the short story format suits her beautifully as well.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)